How to Prevent Heart Disease from Getting Worse

Why are drugs only able to reduce risk by 20% to 30%, while healthy lifestyle choices can eliminate 90% of our risk of having a heart attack? Atherosclerosis, the leading cause of death among men and women, has been found to begin in our teens on the typical American diet. About 3,000 sets of coronary arteries and aortas—the aorta is the body’s main artery—were collected from victims of accidents, homicides, and suicides between the ages of 15 and 34. The findings revealed that fatty streaks in arteries can begin to form in our teens, progress into atherosclerotic plaques in our 20s, become more severe in our 30s, and eventually lead to death. In the heart, atherosclerosis can cause a heart attack. In the brain, it can cause a stroke. See the progression below and at 0:35 in my video Can Cholesterol Get Too Low?.

How prevalent is this? All of the teens they looked at—100% of them—already had fatty streaks building up inside their arteries. Most of them had atherosclerotic plaques that bulged into their arteries by the beginning of their 30s. From ages 15 through 19, their aortas had fatty streaks building up throughout them, but no plaques yet, on average, as seen below and at 1:15 in my video.

By the time they were in their late 20s, fatty streaks had infiltrated their abdominal aorta, and the plaques had begun to appear there in their early 20s. As can be seen below and at 1:25 in my video, their arteries were in bad shape by their early 30s. But that is only the abdominal aorta—the main artery that divides into our legs and runs through the torso. What about the coronary arteries that feed the heart?

Researchers found the same pattern: fatty streaks in teens, early signs of plaque in early 20s that progress with age, and by the early 30s, most people already had plaques in their coronary arteries, as seen below and at 1:47 in my video.

Atherosclerosis starts as early as adolescence.

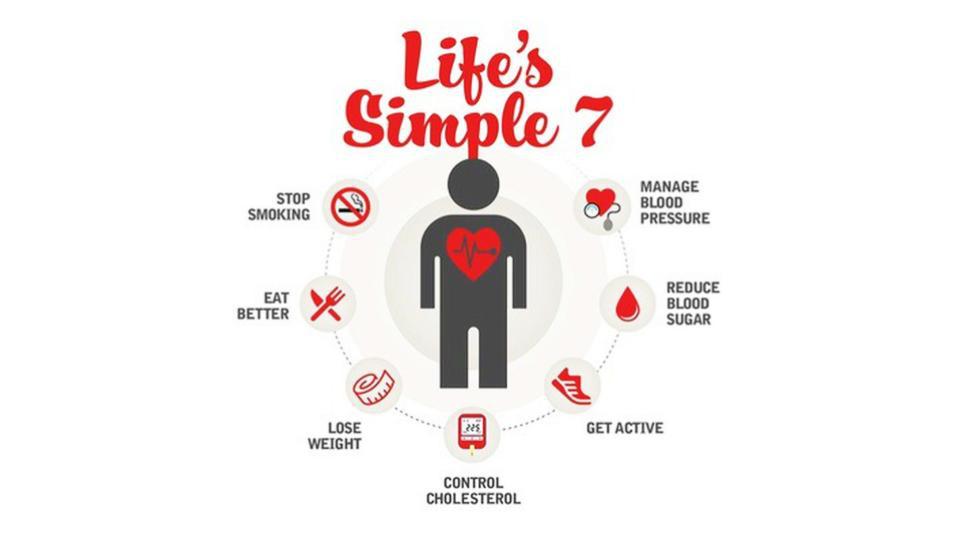

Because of this, treating heart disease should not wait until symptoms appear. If it begins when we are young, we ought to begin treating it when we are young. If you knew you had a cancerous tumor, you wouldn’t want to wait until it grew to a certain size to treat it. If you had diabetes, you wouldn’t want to wait until you started going blind before you did something about it. So, how is atherosclerosis treated? A diet low in cholesterol and saturated fat—a diet low in eggs, meat, dairy, and junk food—helps lower LDL cholesterol. We must “change our lifestyle accordingly, beginning in infancy or early childhood” if we are to put an end to this epidemic. Is such a radical idea totally unworkable? (Eating healthier food? Radical?!) Atherosclerosis is our leading cause of death, and changing our behavior would require a lot of hard work. In the case of cigarettes, we did pretty well, slashing smoking rates and dropping lung cancer rates. Healthy eating is safe, too. Even strictly plant-based diets are suitable for all life stages, beginning with pregnancy, according to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the world’s largest and oldest nutritionist organization. (NutritionFacts.org is among the websites recommended by the Academy for more information.)

The title of an important study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology declares: “Curing Atherosclerosis Should Be the Next Major Cardiovascular Prevention Goal.” What evidence do we have that a lifelong suppression of LDL will do it? One in fifty African Americans is blessed with a genetic mutation of the gene PCSK9 that results in a 40 percent lifetime reduction in LDL cholesterol levels. In fact, despite having averagely poor cardiovascular risk factors, they were found to have significantly lower rates of coronary heart disease—a risk reduction of 88% compared to those without the genetic mutation. The majority had high blood pressure, were overweight, smoked, and had diabetes. However, this demonstrates how a lifetime of low LDL cholesterol levels can significantly reduce the risk of coronary heart disease, even when multiple risk factors are present. At an average LDL level of 100 mg/dL, compared to 138 mg/dL in those who did not have the genetic mutation, there was a drop of nearly 90% in events like heart attacks and sudden death. Because of this, LDL can fall below even 100 mg/dL. Why does a lucky genetic mutation that results in a 40 mg/dL drop in LDL cholesterol reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by nearly 90%, while statin medications only reduce the risk by about 20%? The most probable explanation? Duration. When it comes to lowering LDL cholesterol, it’s not only about how low it is, but how long it’s been low.

Because of this, adopting a healthy lifestyle can reduce our risk of having a heart attack by about 90%, whereas medication can only reduce it by 20% to 30%. If you’re getting treated with drugs later in life, you may have to get your LDL under 70 mg/dL to halt the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. But if we start making healthier choices earlier, it may be enough to lower LDL cholesterol just to 100 mg/dL, which should be achievable for most of us. That’s consistent with country-by-country data that suggested death from heart disease would bottom out at a population average of about 100 mg/dL, as seen below and at 5:21 in my video.

But that’s only if you can keep your LDL cholesterol down your whole life.

If you plan to take medication later in life to stop the progression of your disease, your LDL levels may need to be below 70 mg/dL. If you want to use drugs to stop a lifetime of bad food choices, you may not reach zero heart disease events until your LDL levels are around 55 mg/dL. If your heart disease is so bad that you’ve already had a heart attack but you’re trying not to die from another one, ideally, you might want to push your LDL down to about 30 mg/dL. Once you get that low, not only would you likely prevent any new atherosclerotic plaques, but you’d also help stabilize the plaques you already have so they’re less likely to burst open and kill you.

Is it even safe to have cholesterol levels that low, though? In other words, can LDL cholesterol ever be too low? We’ll find out next.